Truthfully, fans can hardly conceive the existence of Studio Ghibli without Hayao Miyazaki. After all, is not fortuitous that his most personal character happens to be the studio’s logo. Even something as miniscule as the Studio’s logo, die hard Ghibli fans may distrust films directed by different filmmakers—even if they are produced by the same Studio—as well as the future of a Studio without its master.

However, Miyazaki notwithstanding, Ghibli has been home to a small yet prestigious roster of talented directors whose works have bolstered the studio’s hold on the imaginations of anime aficionados and general movie-goers alike, while cementing its legacy as one of the preeminent purveyors of anime as a global art form over the past 30 years. Here are six of the best Studio Ghibli films that don’t feature Hayao’s name on top billing!

6. The Cat Returns (Hiroyuki Morita, 2002)

It seems that Studio Ghibli has little problem producing spin-offs about one of the many lovely supporting characters found in their major films. However, this is not the case the cat character, Baron, from Whisper to the Heart (1995).

Born as “The cats’ project”—Studio Ghibli’s answer to a Japanese theme park’s persistent request about one short film featuring cats—The Cat Returns satisfied Whisper to the Heart’s fans’ increasing wishes about a film adapted from Shizuku’s novel.

Despite its obvious relation to Whisper to the Heart, The Cat Returns actually has an entirely different motif: the exploitation of the magic reduced to a product of Shizuku’s emerging talent in Whisper to the Heart. Undoubtedly, with this film, Hiroyuki Morita has proved his talent.

The film’s plot follows Haru, a shy high school student who helps a cat, but is captured and taken to a world in which she tries to escape. Facing the marriage of this Prince cat, Haru is trapped in a magical fantasy land ruled by these animals. Haru’s only chance of success is carried, of course, by her association with Baron the cat.

5. From Up on Poppy Hill (Gorō Miyazaki, 2011)

Goro Miyazaki is one of—if not the most—scrutinized of Ghibli’s nascent directors. The son of the master himself, Goro’s body of work has been been hounded by the lofty expectations heaped upon his family name long before even the release of his critically maligned debut, Tales from Earthsea, in 2006.

His follow-up in 2011, From Up on Poppy Hill, is a far stronger showing of his potential for greatness. Set in Yokohama, Japan, at a turning point in the country’s newfound post-war identity, Poppy Hill follows the story of Umi Matsuzaki, a young high school girl who befriends a strong-willed student journalist by the name of Shun Kazama and joins him in his campaign to save their school’s historic yet dilapidated clubhouse from being demolished. As the two rally together the student body to defy the school’s decision, circumstances come to light that threaten to upend their budding relationship. Umi and Shun remain nonetheless steadfast in their resolve to save the clubhouse, all the while searching their hearts in the wake of uncertain revelations.

Though the film is is certainly not without its occasional lulls, it benefits greatly from a storyboard screenplay co-penned by none other than Hayao Miyazaki and Keiko Niwa (The Secret World of Arrietty). Karey Kirkpatrick’s English-adapted screenplay is deserving of special mention, injecting incidental quips of background dialogue throughout the film that are as enlightening as they are hilarious. This may not be Goro’s first great film to step entirely from the shadow of his father’s influence, but the simple exuberant charm of From Up on Poppy Hill bodes well for future efforts.

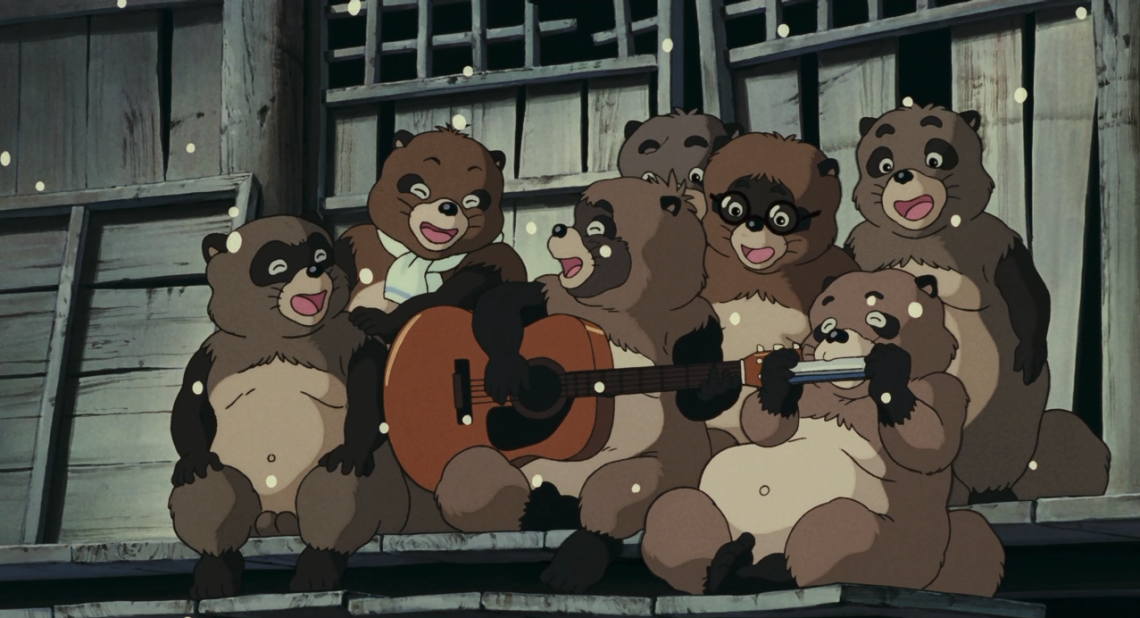

4. Pom Poko (Isao Takahata, 1994)

Takahata’s simplification of the complex folklore surrounding tanukis—Japanese raccoon dogs—is the director’s visionary struggle between nature and civilization, as well as a story about the tension between tradition and innovation. Pom Poko may not be like Miyazaki’s awesome epics Princess Mononoke (1997) and Nausicaa (1970), but the film is a simple, solid, charming story that expresses a perfectly balanced message of optimism.

The plotline follows the aforementioned Japanese raccoon dogs as they carry their hysterical attempts to save their home from the development of an urban neighborhood—symbolic of the destruction of nature. While the complex victory seems inevitable, the human underestimate (or ignore) the tanukis’ supernatural abilities.

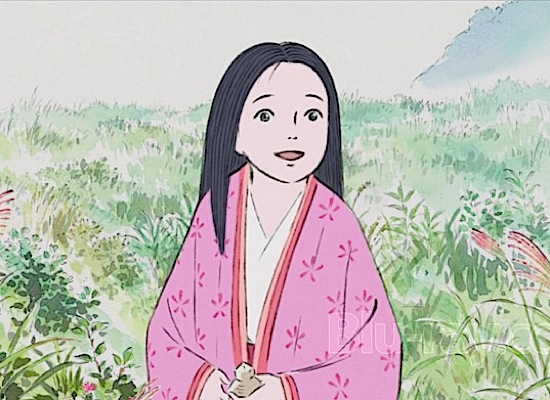

5. The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013)

It’s entirely likely that you could be reading this as ardent fan of Studio Ghibli and Hayao Miyazaki’s films and have no idea who Isao Takahata is. As one of the three founding members of Studio Ghibli, Takahata has directed the second largest number of Ghibli features, eclipsed only by that of his former protege, long-time colleague and unofficial rival. His fifth Studio Ghibli feature and final film, The Tale of Princess Kaguya, was produced alongside and released in the same year as that of Miyazaki’s own parting production, The Wind Rises.

Adapted and inspired by a 10th-century Japanese fable, the film follows the story of the enchanted life and journey of a child who, born from the shoot of a bamboo tree, is discovered and adopted by an elderly bamboo cutter and raised as his own daughter. One of the most captivating dramas Ghibli has produced as of late, The Tale of Princess Kaguya is beautiful both in its story and it’s telling, imbued with an unmistakable aura of impressionistic beauty thanks to its soft watercolor hues and boldly calligraphic compositions.

The sight of Kaguya, surrendering to a fit of desperation, as she storms from the confines of her father’s estate, her ceremonial garments discarded in a regal flourish as she seemingly transforms into a living brushstroke surging like a blur across the canvas of the scene makes for one of the most heart-wrenchingly evocative and stunningly animated sequences in recent memory. The Tale of Princess Kaguya is a declarative testament to why Takahata stands alone and apart from that of his former protege and colleague’s reputation and why he deserves to be touted as a master of the craft of anime in his own right.

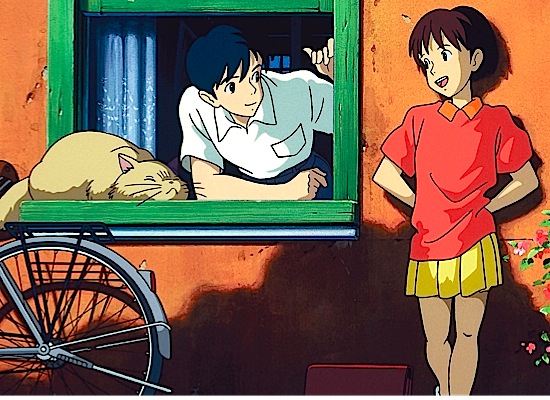

2. Whisper of the Heart (Yoshifumi Kondō, 1995)

Whisper of the Heart is one of Studio Ghibli’s essential titles. The film chronicles the story of Shizuku, a fourteen year old aspiring writer as she notices each and every book she takes from the library has been already read by someone else.

The film provides viewers with a lively girl’s talent that fortunately concedes with her dreams. Shizuku begins to develop her insecurities and openly criticizes conformity. The film is a moving love story that manages to set, if a little, its “cheesy” elements aside.

The film includes a symbolic supporting character—which later prompted Studio Ghibli to laboriously satisfy demanding fans a one short spin-off film. Despite directly lacking the praise of a Studio Ghibli movie, Whisper to the Heart is an excellent film and a product only it could have delivered.

1. Grave of the Fireflies (Isao Takahata, 1988)

Released in 1988 to critical acclaim both in Japan and abroad, Grave of the Fireflies has near-unanimously been touted as Takahata’s masterwork. Adapted from the harrowing autobiographical story of Akiyuki Nosaka, the film presents the tragic and heartwarming account of a brother and sister who attempt to eke out an existence in wake of war and devastation. (Grave’s premise is drawn from the director’s firsthand experience as a survivor of a U.S. air raid on his hometown of Ujiyamada, now Ise, in 1945.)

Although commonly referred to as an anti-war film and hailed as such by its critics, Takahata himself has passionately refuted this definition. Instead, he describes the film as an appeal to empathize with the plight of youths disenfranchised by the indifferent sensibilities of their society and grappling within the throes of great heartache and hardship. Regardless of one’s takeaway, Grave of the Fireflies stands out as a rapturous and achingly somber testament to the stubborn perseverance and indomitable dignity of the human spirit in the wake of insurmountable loss, desolation and despair. It stands proudly as not only one of the best Studio Ghibli films to date, but as one of the greatest animated films of all time.